Crowdfunding Regulation With the aim to overcome existing divergences in national frameworks on crowdfunding, in October 2020 the EU has adopted and published the long awaited final text of the Regulation on crowdfunding service providers… More

Brexit update on cross-border services: MiFID II requirements vs. reverse solicitation

The European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) has recently issued a public statement to remind firms of the MiFID II requirements on the provision of investment services to retail or professional clients by third-country firms. With the end of the UK transition period on December 2020, UK firms now qualify as third-country firms under the MiFID II regime. The third country status of the UK as of 2021 was explicitly confirmed by the German regulator BaFin in a recent publication.

Pursuant to MiFID II, EU Member States may require that a third-country firm intending to provide investment services to retail or to professional clients in its territory have to establish a branch in that Member State or may conduct business requiring a license on a cross-border basis, without having a presence in Germany (so-called notification procedure/EU Passport). However, according to MiFID II, where a retail or professional client established or situated in the EU initiates at its own exclusive initiative the provision of an investment service or activity by a third-country firm, the third country firm is not subject to the MiFID II requirement to establish a branch and to obtain a license (so-called reverse solicitation).

With the end of the UK transition period on December 2020, ESMA notes that some “questionable” practices by firms around reverse solicitation have emerged. For example, ESMA states that some firms appear to be trying to circumvent MiFID II requirements by including general clauses in their Terms of Business or by using online pop-up boxes whereby clients state that any transactions are executed in the exclusive initiative of the client.

With its public statement, ESMA aims to remind firms that pursuant to MiFID II, where a third-country firm solicits (potential) clients in the EU or promotes or advertises investment services in the EU, the investment service is not provided at the initiative of the client and, therefore, MiFID II requirements apply. Every communication means used (press release, advertising on internet, brochures, phone calls etc.) should be considered to determine if the client has been subject to any solicitation, promotion or advertising in the EU on the firm´s investment service or activities. Reverse solicitation only applies if the client actually initiates the provision of an investment service or activity, it does not apply if the investment firm “disguises” its own initiative as one of the client.

However, despite this seemingly rather strict approach of ESMA, reverse solicitation is generally still applicable if a (UK) third-country firm

- only offers services at the sole initiative of the client,

- (only) continues an already existing client relationship or

- continues to inform its clients about its range of products within the scope of existing business relationships (which is often agreed upon in the client´s contract).

It is argued that, for example, in the case of an existing account or deposit or an existing loan agreement that a UK third country firm continues to provide to an EU client after Brexit, no direct marketing or solicitation of the client in the EU takes place. In this case, the third country firm would not have solicited the client.

In a nutshell: What UK firms should consider

The provision of investment services in the EU is subject to license requirements and can include the requirement to establish a branch or a subsidiary in the relevant EU member state. The provision of investment services without proper authorization exposes investment firms to administrative or criminal proceedings. Where a client established in the EU initiates at its own exclusive initiative the provision of an investment service by a third-country firm, such firm is not subject to the requirement to establish a branch or to obtain a license (reverse solicitation). Generally, reverse solicitation also applies when existing client relationships are continued (which have been legitimately established), as the investment firm would not solicit a client in this case.

ESMA update: Impact of Brexit on MiFID II/MiFIR and Benchmark Regulation

At the beginning of October 2020, the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) has updated its previous statements from March and October 2019 on its approach to the application of key provisions of MiFID II/MiFIR and the Benchmark Regulation (BMR) in case of Brexit. As the EU-UK Withdrawal Agreement entered into force on February 2020 and the UK entered a transition period (during which EU law still applies in and to the UK) that will end on 31 December 2020, these statements needed to be revised.

This Blogpost highlights the updated ESMA approach on third-country trading venues regarding the post-trade transparency requirements (MIFID II/MiFIR) and the inclusion of third country UK benchmarks and administrators in the ESMA register of administrators and third country benchmarks (BMR).

MiFID II/MIFIR: Third-country trading venues and post-trade transparency The regulations of MiFID II/MiFIR provide for post-trade transparency requirements. EU investment firms which, for their own account or on behalf of clients, carry out transactions in certain financial instruments traded on a trading venue, are obliged to publish the volume, price and time of conclusion of the transaction. Such publication requirements serve the general transparency of the financial market. As ESMA has already stated in 2017, post-trade transparency obligations also apply where EU investment firms conduct transactions on a third country trading venue.

By the end of the transition period on 31 December 2020, UK trading venues will qualify as third country trading venues. Therefore, if an EU investment firm carries out transactions via a UK trading venue, it is, in general, subject to the MiFID II/MiFIR post-trade transparency obligations.

However, EU-investment firms would not be subject to the MiFID II/MiFIR post-trade transparency requirements if the relevant UK trading venue would already be subject to EU-comparable regulatory requirements itself. This would be the case if the trading venue would be subject to a licensing requirement and continuous monitoring and if a post-trade transparency regime would be provided for.

In June 2020, ESMA published a list of trading venues that meet these requirements. While the UK was a member of the EU and during the transition period, ESMA did not asses UK trading against those criteria. However, ESMA intends to perform such assessment of UK trading venues before the end of the transition period. Transactions executed by an EU investment firm on a UK trading venue that, after the ESMA assessment, would be included in the list, will not be subject to MiFID II/MiFIR post-trade transparency. In this case, sufficient transparency requirements would already be ensured by the comparable UK regime. However, any transactions conducted on UK trading venues not included in the ESMA list on EU-comparable trading venues will by the end of the transition period be subject to the MiFID II/MiFIR post-trade transparency rules.

BMR: ESMA register of administrators and third country benchmarks

Supervised EU-entities can only use a benchmark in the EU if it is provided by an EU administrator included in the ESMA register of administrators and third country benchmarks (ESMA Register) or by a third country administrator included in the ESMA Register. This is to ensure that all benchmarks used within the EU are subject to either the BMR Regulation or a comparable regulation.

So far, UK administrators qualified as EU administrators and have been included in the ESMA Register. After the Brexit transition period, UK administrators included in the ESMA register will be deleted as the BMR will by then no longer be applicable to UK administrators. UK administrators that were originally included in the ESMA Register as EU administrators, will after the Brexit transition period qualify as third country administrators. The BMR foresees different regimes for third country administrators to be included in the ESMA Register, being equivalence, recognition or endorsement.

“Equivalence” must be decided on by the European Commission. Such decision requires that the third country administrator is subject to a supervisory regime comparable to that of the BMR. So far, the European Commission has not yet issued any decision on the UK in this respect. Until an equivalence decision is made by the European Commission, UK administrators therefore have (only) two options if they want their benchmarks eligible for being used in the EU: They/their benchmarks need to be recognized or need to be endorsed under the BMR.

Recognition of a third country administrator requires its compliance with essential provisions of the BMR. The endorsement of a third country benchmark by an administrator located in the EU is possible if the endorsing administrator has verified and is able to demonstrate on an on-going basis to its competent authority that the provision of the benchmark to be endorsed fulfils, on a mandatory or on a voluntary basis, requirements which are at least as stringent as the BMR requirements.

However, the BMR provides for a transitional period itself until 31 December 2021. A change of the ESMA Register would not have an effect on the ability of EU supervised entities to use the benchmarks provided by UK administrators. During the BMR transitional period, third country benchmarks can still be used by supervised entities in the EU if the benchmark is already used in the EU as a reference for e.g. financial instruments. Therefore, EU supervised entities can until 31 December 2021 use third country UK benchmarks even if they are not included in the ESMA Register. In the absence of an equivalence decision by the European Commission, UK administrators will have until the end of the BMR transitional period to apply for a recognition or endorsement in the EU, in order for the benchmarks provided by these UK administrators to be included in the ESMA Register again.

Brexit, still great uncertainty

Currently, the whole Brexit situation is fraught with great uncertainty due to the faltering political negotiations. The updated ESMA Statement contributes to legal certainty in that it clearly sets out the legal consequences that will arise at the end of the transition period. This is valuable information and guidelines for all affected market participants, who must prepare themselves in time for the end of the transition period and take appropriate internal precautions.

EBA´s New Role in Anti-money Laundering and Countering the Financing of Terrorism

At the turn of the year, there have been some new developments in anti-money laundering (AML) law at both German and EU level. Part 1 of our series dealt with the changes at German law resulting from the implementation of the Fifth EU Anti-Money Laundering Directive. Part 2 sheds some light on the European Banking Authority’s (EBA) new leading role in anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism (CFT).

What is changing in the approach to AML/CFT?

In 2019, the EU legislator gave EBA a legal mandate to preventing the use of the financial system for the purposes of money laundering and terrorist financing and to leading, coordinating and monitoring the AML/CFT efforts of all EU financial service providers and competent authorities. The law implementing EBA´s new powers came into effect on 1 January 2020.

However, assigning EBA a leading role in AML/CFT will not change the EU´s general approach to AML/CFT, which remains based on a minimum harmonisation directive and an associated strong focus on national law and direct supervision of financial institutions by national competent authorities. This reduces the influence and the degree of convergence and consistency EBA´s work can achieve from the outset.

To the extent legally possible, EBA will use its new role to

- lead the establishment of AML/CTF policy and support its effective implementation by competent authorities and financial institutions;

- coordinate AML/CFT measures by fostering effective cooperation and information exchange between all relevant authorities;

- monitor the implementation of EU AML/CFT standards to identify vulnerabilities in competent authorities´ approaches to AML/CFT supervision and to mitigate them before money laundering and financing of terrorism risks materialise.

How will EBA lead on AML/CFT?

To fulfill its new leading role, EBA will focus on two key point: developing an EU-wide AML/CFT policy and ensuring a consistent supervision by national competent authorities. EBA intends to develop such EU-wide AML/CFT policy through standards, guidelines or opinions where this is provided for in EU law as well as on its own initiative where it identifies, for example, gaps in competent authorities´ supervision. In 2020, EBA will be setting clear expectations on the components of an effective risk-based approach with targeted revisions to the core AML/CFT guidelines: the Risk Factors Guidelines and the Risk-Based Supervision Guidelines.

EBA intends to foster a consistent supervision by national competent authorities by assisting them through training, bilateral support and detailed bilateral feedback on their approach to the AML/CFT supervision of banks.

What will EBA do to coordinate?

To coordinate the European work against money laundering and terrorism financing, EBA will focus to coordinate national competent authorities´ AML/CFT supervision by fostering effective cooperation and information exchange. To achieve its goal, the EBA will set up a permanent internal AML/CFT standing committee (AMLSC). The AMLSC will bring together, inter alia, representatives of all AML/CFT competent authorities from Member States, along with representatives from ESMA and EIOPA, the Commission and the European Central Bank. Its main task will be to provide subject matter expertise. It will also serve as a forum to facilitate information exchange and ensure effective coordination and cooperation to achieve consistent outcomes in the EU’s work against money laundering and terrorism financing. The AMLSC has met for the first time in February 2020.

In addition to the AMLSC, EBA will create a new AML/CFT database. This database will not only contain information on AML/CFT weaknesses in individual financial institutions and measures taken by competent authorities to correct those shortcomings, but EBA will use it to meet wider AML/CFT information and data need to supports its objectives on AML/CFT work. EBA will draft two regulatory technical standards that will specify the core information that competent authorities must submit to the date base and how EBA will analyse the obtained information and make it available to competent authorities.

What will EBA do to monitor?

One main tool for EBA to monitor the implementation of EU AML/CFT standards will be using information from the new database and to ask national competent authorities to take action if EBA has the indication that a financial institution´s approach to AML/CFT materially breaches EU law. EBA envisages to use this new tool proactively to ensure that AML/CFT risks are addressed by competent authorities and financial institutions in a timely and effective manner. This approach aims to rectify shortcomings at the level of financial institutions; they do not, however, serve to establish whether or not a competent authority may be in breach of Union law.

The difference EBA´s new role will make

As the national implementation of the Fifth European AML Directive and the EBA´s new leading role show, effective AML/CFT measures remain in the focus of the EU legislator, not least due to political developments (terrorist attacks in France, “Panama Papers” etc.). Market participants should prepare themselves for stricter audits by their competent national authorities on AML/CFT compliance. For example, the German Federal Financial Supervisory Authority (Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht – BaFin) has announced AML/CFT as one of its focuses of its supervisory practice for 2020. By assigning a leadership role to EBA, European efforts to prevent money laundering will in future be better coordinated, bundled and consistently implemented throughout the European financial market and therefore, hopefully, be more effective. However, we need to keep in mind that BaFin and subsequently also EBA are only part of the European and national AML regime. In Germany, for example, the FIU has a leading role in AML activities. An overview of the authorities involved can be found here.

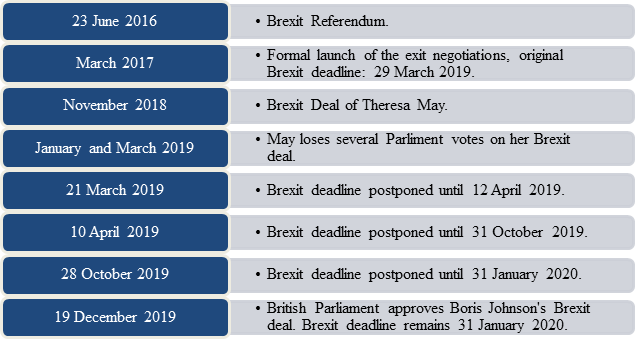

Brexit Update: What Happened So Far

The last year of the old decade brought so many twists and turns on the subject of Brexit that one could easily lose track. Hence, our first blogpost of the new decade will shed some light on the current Brexit situation and the next steps currently planned by British and European politicians. As always, we will focus in particular on the effects on the financial market.

Current Situation: What Will Happen Now?

Since the British Parliament approved Johnson´s Brexit deal in December 2019, the UK will leave on 31 January 2020. An 11-month transition phase will then come into force: the UK will remain in the EU single market and the customs union until the end of 2020. During this period everything will remain mostly the same for the time being.

During the transition period, the EU and the UK will have to reorganise their relations with each other, with future economic relations as well as security and defence cooperation being key issues. First of all, a comprehensive Free Trade Agreement is to be concluded, which can above all prevent customs duties at the borders. But other economic areas, such as the financial market in particular, must also be regulated, either as part of the Free Trade Agreement (which would be unusual from a legal perspective) or through a separate agreement.

11 months are a short time and one may have doubts as to whether this time will be sufficient. The European Commission is already considering equivalence assessments for the financial market. However, there will be not ONE equivalent decision (see here) for an earlier analysis of the equivalence principle of the EU). There are currently around 40 equivalence areas which need to be assessed in each case. Most equivalence decisions provide for prudential benefits, some provide for burden reduction and some can lead to market access. There will also have to be close cooperation between the UK and EU financial supervisory authorities. During the assessment process the EU will look at UK legislation and supervision and will take a risk-based approach – as for all other third countries. This means that the higher the possible impact on the EU market, the more granular will the assessment be conducted. In case the UK will stick with the current EU regulation, this will be an easier task. But as soon as the UK will break new ground to make the UK financial market more attractive the impact on the equivalent status will need to be considered.

It can be assumed that the German Federal Financial Supervisory Authority (Bundesanstalt für Finanzdiensteistungsaufsicht – BaFin) and the other European financial supervisory authorities will monitor the negotiations regarding a financial market agreement very closely during the transition phase and will adapt and communicate their intentions for action accordingly.

To Be Continued

Although a hard Brexit has been avoided, there will still be uncertainties about future relations between the EU and the UK. Financial market participants should follow the negotiations between the EU and the UK closely and not rely on the fact that a financial market agreement can be concluded successfully in the short transition period.

EBA’s Action Plan on Sustainable Finance

Climate change and the response to it by the public sector and society in general have led to an increasing relevance of environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors for financial markets. It is, therefore, essential that financial institutions are able to measure and monitor the ESG risks in order to deal with risks stemming from climate change (learn more about climate change related risks in our previous Blogpost.

To support this, on 6 December 2019, the European Banking Authority (EBA) published its Action Plan on Sustainable Finance outlining its approach and timeline for delivering mandates related to ESG factors. The Action Plan explains the legal bases of the EBA mandates and EBA´s sequenced approach to fulfil these mandates.

Why is EBA in charge ? EBA mandates on sustainable finance

The EBA´s remit and mandates on ESG factors and ESG risks are set out in the following legislative acts:

- the amended EBA Regulation;

- the revised Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR II) and Capital Requirements Directive (CRD V);

- the new Investment Firms Regulation (IFR) and Investment Firms Directive (IFD) and

- the EU the Commission´s Action Plan: Financing Sustainable Growth and related legislative packages.

These legislatives acts reflect a sequenced approach, starting with the mandates providing for the EBA to oblige institutions to incorporate ESG factors into their risk management as well as delivering key metrics in order to ensure market discipline. The national supervisory authorities are invited to gain an overview of existing ESG-related market risks. In a second step, the EBA will develop a dedicated climate change stress test that institutions should use to test the impact of climate change related risks on their risk-bearing capacity and to take appropriate precautions. The third step of the work will look into the evidence around the prudential treatment of “green” exposures.

The rationale for this sequencing is the need firstly to understand institutions´ current business mix from a sustainability perspective in order to measure and manage it in relation to their chosen strategy, which can then be used for scenario analysis and alter for the assessment of an appropriate prudential treatment.

Strategy and risk management

With regard to ESG strategy and risk management, the EBA already included references to green lending and ESG factors in its Consultation paper on draft guidelines on loan origination and monitoring which will apply to internal governance and procedures in relation to credit granting processes and risk management. Based on the guidelines the institutions will be required to include the ESG factors in their risk management policies, including credit risk policies and procedures. The guidelines also set out the expectation that institutions that provide green lending should develop specific green lending policies and procedures covering granting and monitoring of such credit facilities.

In addition, based on the mandate included in the CRD V, the EBA will asses the development of a uniform definition of ESG risks and the development of criteria and methods for understanding the impact of ESG risks on institutions to evaluate and manage the ESG risks.

It is envisaged that the EBA will first publish a discussion paper in Q2-Q3/2020 seeking stakeholder feedback before completing a final report. As provided for in the CRD V, based on the outcome of this report, the EBA may issue guidelines regarding the uniform inclusion of ESG risks in the supervisory review and evaluation process performed by competent authorities, and potentially also amend or extend other policies products including provisions for internal governance, loan origination and outsourcing agreements.

Until EBA has delivered its mandates on strategy and risk management, it encourages institutions to act proactively in incorporating ESG considerations into their business strategy and risk management as well as integrate ESG risks into their business plans, risk management, internal control framework and decision-making process.

Key metrics and disclosures

Institutions disclosures constitute an important tool to promote market discipline. The provision of meaningful information on common key metrics also distributes to making market participants aware of market risks. The disclosure of common and consistent information also facilitates comparability of risks and risks management between institutions, and helps market participants to make informed decisions.

To support this, CRR II requires large institutions with publicly listed issuances to disclose information on ESG risks and climate change related risks. In this context, CRR II includes a mandate to the EBA according to which it shall develop a technical standard implementing the disclosure requirements. Following this mandate, EBA will specify ESG risks´ disclosures as part of the comprehensive technical standard on Basel´s framework Pillar 3.

Similar mandates are contained in the IFR and IFD package. The IFD mandate for example requires EBA to report on the introduction of technical criteria related to exposures to activities associated substantially with ESG objectives for the supervisory review and evaluation process of risks, with a view to assessing the possible sources and effects of such risks on investment firms.

Until EBA has delivered its mandates, it encourages institutions to continue their work on existing disclosure requirements such as provided for in the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) as well as participation in other initiatives. EBA also encourages institutions to prioritise the identification of some simple metrics (such as green asset ratio) that provide transparency on how climate change-related risks are embedded into their business strategies, decision-making process, and risk management.

Stress testing and scenario analysis

The EBA Regulation includes a specific reference to the potential environmental-related systemic risk to be reflected in the stress-testing regime. Therefore, the EBA should develop common methodologies assessing the effect of economic scenarios on an institutions´ financial position, taking into account, inter alia, risks stemming from adverse environmental developments and the impact of transition risk stemming from environmental political changes.

Also the CRD V mandate requires EBA to develop appropriate qualitative and quantitative criteria, such as stress testing processes and scenario analysis, to asses the impact of ESG risks under scenarios with different severities. Hence, EBA will develop a dedicated climate stress test with the main objective of identifying banks´ vulnerabilities to climate-related risks and quantifying the relevance of the exposures that could potentially hit by climate change related risks.

Until delivering its mandates, EBA encourages institutions to adopt climate change related scenarios and use scenario analysis as an explorative tool to understand the relevance of the exposures affected by and the potential magnitude of climate change related risks.

Prudential treatment

The mandate in the CRR II asks EBA to assess if a dedicated prudential treatment of exposures to assets or activities associated with environmental or social objectives would be justified. The findings should be summarised in a report based on the input of a first to be published discussion paper.

Upshot

Between 2019 and 2025, the EBA will deliver a significant amount of work on ESG and climate change related risks. The obligations for institutions with regard to a sustainable financial economy and a more conscious handling of climate change related risks are becoming increasingly concrete. Institutions should take the EBA’s encouragement seriously and consider applying the measures recommended by the EBA prior to the publication of any guidelines, reports or technical standards.

ESMA updated AIFMD and UCITS Q&As

On June 4, 2019 ESMA published updates questions and answers on the application of the AIFM Directive (available here) and the UCITs Directive (available here). ESMA’s intention of publishing und regularly updating the Q&A documents ensures common supervisory approaches and practices in relation to both the AIFM Directive and the UCITS Directive and their implementing measures.

The latest update refers to the depositories and the possibilities to delegate the safekeeping of assets of the funds. ESMA clarifies that supporting tasks that are linked to depositary tasks such as administrative or technical functions performed as part of the depositary tasks could be entrusted to third parties where all of the following conditions are met:

- the execution of the tasks does not involve any discretionary judgement or interpretation by the third party in relation to the depositary functions;

- the execution of the tasks does not require specific expertise in regard to the depositary function; and

- the tasks are standardised and pre-defined.

Where depositaries entrust tasks to third parties and give them the ability to transfer assets belonging to AIFs or UCITS without requiring the intervention of the depositary, these arrangements are subject to the delegation requirements, in Germany subject to Para. 36 KAGB.

Another question relates to the supervision of branches of depositories. The AIFM Directive, the UCITS Directive, the CRD and the MiFID II do not grant any passporting rights for depositary activities in relation to safekeeping assets for AIFs or UCITS. Branches of depositories located in the home Member State of the AIF or UCITS that is not the home Member State of the depositary’s head office may also be subject to local authorisation in order to perform depositaries activities in relation to AIFs or UCITS. In this case, the competent authority for supervising the activities in relation to AIFs or UCITS is the one located in the Member State of the depository’s branch.

The guidance provided by ESMA in the Q&A documents for AIFs and UCITS regarding the depository function do not contain any surprising elements but further strengthen the harmonized interpretation and application of the AIFM and UCITS Directives in Europe.

Benchmarks Regulation: Updated ESMA Q&A bring more clarity about input data used for regulated-data benchmarks

To provide benchmarks, administrators rely on input data from contributors. If the contributors are regulated, the benchmarks created with their data qualify as regulated-data benchmarks. The updated Question and Answers (Q&A) of January 30, 2019 from the European Securities and Markets authority (ESMA) provide, inter alia, answers to three questions regarding input data used for regulated-data benchmarks which have been raised frequently in the market (Q&A available here). This blogpost will present these questions as well as ESMA´s answers. Beforehand, it gives a short overview of the Benchmarks Regulation´s regulatory background and explains what input data means.

Regulatory background of the Benchmarks Regulation

Regulation (EU) 2016/1011 concerning indices used as a reference value or as a measure of the performance of an investment fund for financial instruments and financial contracts (Benchmarks Regulation – BMR) sets out the regulatory requirements for administrators, contributors and users of an index as a reference value for a financial product with respect to both the production and use of the indices and the data transmitted in relation thereto. It is the EU’s response to the manipulation of LIBOR and EURIBOR. The BMR aims to ensure that indices produced in the EU and used as a reference value cannot be subject to such manipulation again. In previous blogposts on the BMR, we have already dealt with the requirements for contingency plans and non-significant benchmarks (ESMA publishes Final Report on Guidelines on non-significant benchmarks- Part 1 and Part 2.)

Input data

For a benchmark to be created, the administrator, i.e. the person/entity who has control over the provision of the reference value, relies on data he receives from contributors. These data used by an administrator to determine a benchmark in relation to the value of one ore more underlying asset or prices qualify as input data under the BMR.

With this in mind, what are the market-relevant questions regarding input data that are answered in the updated Q&A by ESMA?

- Can a benchmark qualify as a regulated-data benchmark if a third party is involved in the process of obtaining the data?

Under the rules of the BMR, a benchmark only qualifies as a regulated-data benchmark if the input data is entirely and directly submitted by contributors who are themselves regulated (e.g. trading venues). Since the input data come exclusively from entities that are themselves subject to regulation, the BMR sets fewer requirements for the provision of benchmarks from regulated data than for other benchmarks. This precludes, in principle, the involvement of any third party in the data collection process. The data should be sourced entirely and directly from regulated entities without the involvement of third parties, even if these third parties function as a pass-through and do not modify the raw data.

However, if an administrator obtains regulated data through a third party service provider (such as data vendor) and has in place arrangements with such service provider that meet the outsourcing requirements of the BMR, the administrator´s benchmark still qualifies as regulated-data benchmark. The third party being subject to the BMR´s outsourcing requirements ensures a quality of the input data contributed by this third party comparable to the quality of the input data contributed by a regulated entity.

- Can NAV of investment funds qualify as benchmark?

The net asset value (NAV) of an investment fund is its value per share or unit on a given date or a given time. It is calculated by subtracting the fund´s liabilities from its assets, the result of which is divided by the number of units to arrive at the per share value. It is most widely used determinant of the fund´s market value and very often it is published on any trading day.

But, according to the BMR stipulations, the NAVs of investment funds are data that, if used solely or in conjunction with regulated data as a basis to calculate a benchmark, qualify the resulting benchmark as a regulated-data benchmark. The BMR therefore treats NAVs as a form of input data that is regulated and, consequently, should not be qualified as indices.

- Can the methodology of a benchmark include factors that are not input data?

The methodology of a benchmark can include factors that are not input data. These factors should not measure the underlying market or economic reality that the benchmark intends to measure, but should instead be elements that improve the reliability and representativeness of the benchmark. This should be, according to ESMA, considered as the essential distinction between the factors embedded in the methodology and input data.

For instance, the methodology of an equity benchmark may include, together with the values of the underlying shares, a number of other elements, such as the free-float quotas, dividends, volatility of the underlying shares etc. These factors are included in the methodology to adjust the formula in order to get a more precise quantification of the equity market that the benchmark intends to measure, but they do net represent the price of the shares part of the equity benchmark.

Upshot

The updated ESMA Q&A provide more clarity for market participants on the understanding of input data and its use for regulated-data benchmarks. ESMA´s input will facilitate dealing with the regulatory requirements of the BMR, at least with regard to input data.

ESAs publish joint report on regulatory sandboxes and innovation hubs – Part 2

On January 7th 2019 the European Supervisory Authorities (ESAs) (consisting of ESMA, EBA and EIOPA) published as part of the European Commission’s FinTech Action Plan a joint report on innovation facilitators (i.e. regulatory sandboxes and innovation hubs). The report sets out a comparative analysis of the innovation facilitators established to date within the EU including the presentation of best practices for the design and operation of innovation facilitators.

We take the report as an occasion to present both innovation hubs and regulatory sandboxes in a two-part article. After we highlighted innovation hubs in Part 1, Part 2 will shed some light on regulatory sandboxes.

Regulatory sandboxes – What they are and what their goals are

The EU Commission´s FinTech Action plan provides for regulatory sandboxes to create an environment in which supervision is specifically tailored to innovative firms or services. ESMA’s joint report follows on from the FinTech Action plan and investigates the previous equipment and experience with regulatory sandboxes.

In detail, a regulatory sandbox provides a scheme to enable regulated and unregulated entities to test, pursuant to a specific testing plan agreed and monitored by the competent authority, innovative financial products, financial services or business models under real regulatory conditions before they bring the products to market.

The aim of a regulatory sandbox is to provide a monitored space in which competent authorities and firms can better understand the opportunities and risks presented by innovations and their regulatory treatment through a testing phase. Also, firms can assess the viability of innovative positions, in particular in terms of their application of and their compliance with regulatory and supervisory requirements. However, regulatory sandboxes do not entail the disapplication of regulatory requirements that must be applied as a result of EU law. On the contrary, the baseline assumption for regulatory sandboxes is that firms are required to comply with all relevant regulatory requirements applicable on the activity they are undertaking. The main goal of the regulatory sandboxes, as with the innovation hubs, is therefore to enhance the firms’ understanding of the relevant regulatory issues and, on the other hand, to enhance the competent authorities’ understanding of innovative financial products.

Where they exist and who can participate

At the date of the ESA report, five competent authorities reported operational regulatory sandboxes: Denmark, Lithuania, Netherlands, Poland and UK. The sandboxes are open to incumbent institutions, new entrants and other firms. Moreover, the sandboxes are not limited to a certain part of the financial sector, rather they are cross-sectored (e.g. banking, investment services, payment services and insurances).

How does a regulatory sandbox work exactly?

Typically, regulatory sandboxes involve several phases which can be described as (i) an application phase, (ii) a preparation phase, (iii) a testing phase and (iv) an exit or evaluation phase.

In the following, we briefly describe the steps taken in each phases either by the firm or by the competent authority.

Application phase

Firms interested in participating on a regulatory sandbox must submit an application by the competent authority. The applications received are judged by the competent authority against set, transparent, publicly available criteria. These criteria are, e.g. (i) the scope of the propositions, i.e. does the firm’s business model to be tested in the regulatory sandbox involve regulated financial services, (ii) the innovativeness of the firm’s proposition and (iii) the readiness of the firm to test its proposition. Whether the company is ready for a regulatory test phase in the sandbox is judged on the basis whether or not the firm has, e.g., developed a business plan or has obtained the appropriate software license.

Preparation phase

During the preparation phase, the competent authorities work with the firms deemed to be eligible to participate in the regulatory sandboxes to determine:

- whether or not the proposition to be tested involves a regulated activity. If this is the case and the firm does not already hold the appropriate license, the firm will be required to seek the appropriate license in order to progress to the testing phase,

- if any operational requirements need to be put in place to support the test (e.g. systems and controls, reporting),

- the parameters for the test (such as number of clients, restrictions on serving specific clients, restrictions on disclosure),

- the plan for the engagement between the firm and the competent authority during the testing phase.

Testing phase

The testing phase allows sufficient opportunity for the proposition to be fully tested and for the opportunities and risks to be explored. Throughout the testing phase, the firm is expected to communicate with the competent authority through a direct on-site presence, meetings, regulator calls or pre-agreed written reports. According the ESAs report, the supervision during the testing phase in a regulatory sandbox is experienced as a more intense supervision by the competent authority than the usual supervisory engagement outside the sandbox.

From the perspective of the competent authority, the value of the testing phase in the regulatory sandbox can be found in the opportunity to understand the application of the regulatory framework with regard to the innovative proposition and in the opportunity to built in appropriate safeguards for innovative propositions, for example with regard to consumer protection considerations. On the other hand, the value for the firms can be found in gaining better appreciation of the application of the regulatory scheme and supervisory expectations regarding the innovative propositions.

Evaluation phase

In the evaluation phase, the firm either submits to the authority a final report so that an assessment of the test can be carried out, or the competent authority will evaluate the success of the test by drawing on input provided by the firm. It should be noted that the test can be considered a success in many ways. Thus, not only the result that the product can be successfully established on the market under the tested regulatory conditions can be regarded as a success, but also the recognition that it is not possible for a proposition to be viably applied at the markets in the light of the existing regulatory and supervisory obligations.

Why is there no regulatory sandbox in Germany?

Unlike in Denmark, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Poland and the UK, the German Federal Financial Supervisory Authority (Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht – BaFin) has not set up a regulatory sandbox in Germany. In the past, BaFin promoted the view that each market participant needs to observe all regulatory requirements. One of the reasons behind that was and is the customer protection and equal treatment of companies. BaFin cites the fact that the sandbox model promotes conflicts of interest as the main reason for this:[1] after all, how would a supervisor behave if a FinTech, which BaFin had previously taken care of in its sandbox, did not treat his customers the way it should?[2]

Upshot

Regulatory sandboxes offer interested companies a good opportunity to test the products they develop under real regulatory conditions and in a supervisory environment specially tailored to innovative companies and therefore to better understand all (regulatory) possibilities and risks on the innovative product. It should be emphasized though that regulatory sandboxes do not apply a supervision light; rather all regulatory requirements must be fulfilled, especially with regard to a required authorisation. However, precise testing under real regulatory conditions and close monitoring by the supervisory authority can provide companies with important insights into their innovative products.

[1] New Year’s press reception of BaFin 2016, Speech by Felix Hufeld, President of BaFin, in Frankfurt am Main on 12 January 2016, available at https://www.bafin.de/SharedDocs/Veroeffentlichungen/DE/Reden/re_160112_neujahrspresseempfang_p.html (accessed on 22 January 2019).

[2] New Year’s press reception of BaFin 2016, Speech by Felix Hufeld, President of BaFin, in Frankfurt am Main on 12 January 2016, available at https://www.bafin.de/SharedDocs/Veroeffentlichungen/DE/Reden/re_160112_neujahrspresseempfang_p.html (accessed on 22 January 2019).

ESAs publish joint report on regulatory sandboxes and innovation hubs – Part 1: Innovation hubs available for enquiries

On January 7th 2019, the European Supervisory Authorities (ESAs) (consisting of the European Securities and Markets Authority, the European Banking Authority and the European Insurance and Occupational Pension Authority) published as part of the European´s Commission FinTech Action Plan e a joint report on innovation facilitators (i.e. regulatory sandboxes and innovation hubs) available here . The report sets out a comparative analysis of the innovation facilitators established to date within the EU including the presentation of best practices for the design and operation of innovation facilitators.

We take the report as an occasion to present both innovation hubs and regulatory sandboxes in a two-part article. In Part 1 we will discuss what exactly innovation hubs are, what goals they pursue and how they are structured in Germany. Part 2 will then deal with the regulatory sandboxes.

Innovation hubs – What they are and what their goals are

It is often difficult for companies to obtain binding statements on regulatory requirements when a business model is still developing. Innovation hubs create a formal framework that considerably simplifies the exchange between innovators and supervisors, thereby promoting market access.

Innovation hubs provide a dedicated point of contact for firms to raise enquiries with competent authorities on Fin Tech-related issues to seek non-binding guidance on the conformity of innovative financial products, financial services, business models or delivery mechanisms with licensing or registration requirements and regulatory and supervisory expectations. In general, the innovation hubs are available to companies as a user interface at the relevant national authority. In Germany, the innovation hub is located at the Federal Financial Supervisory Authority (Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht – BaFin) and is available here. A total of twenty-one EU Member States have established innovation hubs.[1]

Innovation hubs have been set up to enhance firms´ understanding of the regulatory and supervisory expectations regarding innovative business models, products and services. To achieve this goal, firms are provided with a contact point for asking questions of, and initiate dialogue with, competent authorities regarding the application of regulatory and supervisory requirements to innovative business models, financial products, services and delivery mechanisms. For example, the innovation hubs provide firms with non-binding guidance on the conformity of their proposed business model with regulatory requirements; specifically, whether or not the proposition would include regulated activities for which authorisation is required.

Who can participate and how does an innovation hub work exactly?

In the following, we explain which companies can participate in the innovation hubs and describe how exactly the communication between the companies and the innovation hub takes place.

Scope

The innovation hubs are open to all firms, whether incumbents or new entrants, regulated or unregulated which adopt or consider to adopt innovative products, services, business models or delivery mechanisms.

Communication process between firms and competent authorities

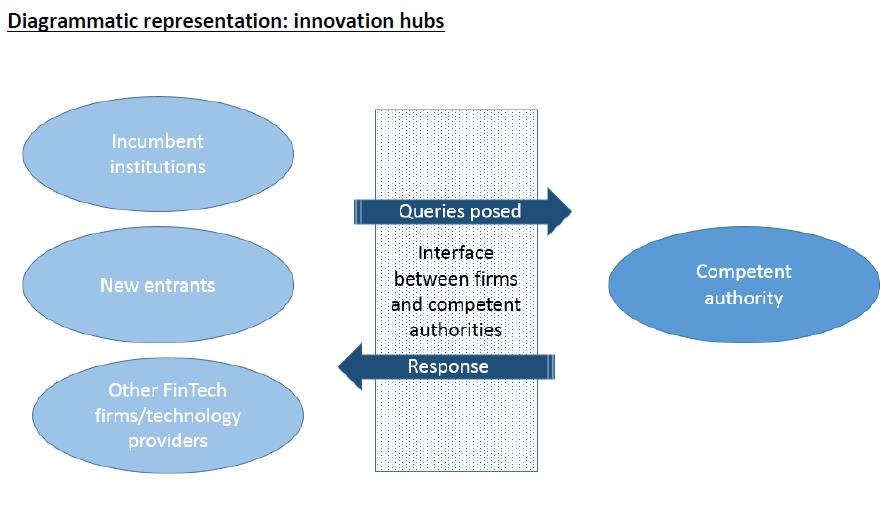

The following ESA graph illustrates the communication process between the firms and the competent authority using the innovation hub. The individual phases of the communication process are explained below. [2]

Submission of enquiries via interface

In order to submit enquiries, all innovation hubs set up in the EU Member States offer interested companies user interfaces through which contact can be established with the respective supervisory authority. This can be done e.g. by telephone or electronically, but also via online meetings or websites. Some innovation hubs also offer the possibility of organising physical meetings. In Germany, BaFin provides an electronic contact form in which both the company data and the planned business model can be presented and transmitted to BaFin. The contact form is available here.

Assigning the request to the relevant point of contact within the competent authority

As soon as the contact has been established and the request has been submitted, typically the authority conducts a screening process to determine how best to deal with the queries raised. In this process, the authority considers factors such as the nature of the query, its urgency and its complexity, including the need to refer the query to other authorities, such as data protection authorities.

Providing responses to the firms

Depending on the nature of the enquiries raised, several information exchanges between the firm and the competent authority may take place. Responses to firms may be routed to different channels such as meetings, telephone calls or email. Typically, the responses provided via the innovation hub are to be understood as preliminary guidance based solely on the facts established in the course of the communications between the firms and the competent authority. The companies can use the information gained to better understand the regulatory requirements for their planned business model and develop it further on this basis.

Follow-up actions

Some authorities offer follow-up actions within their innovation hubs. Especially if the communication process between the company and the authority shows that the business model of the company includes a regulated activity. In this case, some competent authorities may provide support within the authorisation process (e.g. dedicated point of contact, guidance on the completion of the application form).

Previous experiences on the use of innovation hubs

Although innovation hubs are available to all market participants, according to the ESA report, three categories of companies in particular use the innovation hubs: (i) start-ups, (ii) regulated entities that are already supervised by competent authorities and are considering innovation products or services and (iii) technology providers offering technical solutions to institutions active in the financial markets.

Typically, the firms use the innovation hub to seek information about the following: (i) whether or not a certain activity needs authorisation and, if so, information about the licensing process and the regulatory and supervisory obligations, (ii) whether or not anti-money laundering issues arise, and (iii) the applicability of consumer protection regulation and (iv) the application of regulatory and supervisory requirements (e.g. systems and controls).

Upshot

Innovation hubs

provide companies with a good opportunity to interact with regulators via a user-friendly

platform. They can therefore clarify the regulatory requirements for the

products they plan to develop at an early stage and incorporate them into their

business planning. By setting up innovation hubs, especially for young and

dynamic (FinTech-) start-ups, the inhibition threshold to contact the

supervisory authority is significantly lowered, especially because predefined

user interfaces can be used.

[1] Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Germany, Denmark, Estonia, Spain, Finland, France, Hungary, Ireland, Iceland, Italy, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Latvia, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Sweden, UK.

[2] Source: ESA Report FinTech: Regulatory sandboxes and innovation hubs.

ESMA Supervisory briefing on the supervision of non-EU branches of EU firms providing investment services and activities

With Brexit coming up, many companies, especially those in the financial sector, have taken precautions and relocated their EU head offices to one of the 27 remaining EU member state to ensure that, whatever the outcome of the Brexit negotiations, they will have access to the European single market. Offices in the UK, which will qualify as a third country after Brexit, will often be operated as branches.

On February 6, 2019, ESMA published its MIFID II Supervisory briefing on the supervision of non-EU branches of EU firms providing investment services and activities. Through its new Supervisory briefing, ESMA aims to ensure effective oversight of the non-EU branches by the competent authority of the firm´s home member state.

This article provides an overview of the measures proposed by ESMA to national regulatory authorities, divided into three areas: (i) ESMA´s supervisory expectations in relation to the authorisation of investment firms; (ii) the supervision of ongoing activities of non-EU branches by the competent authority; and (iii) ESMA´s proposed supervisory activity of the competent authority.

Supervisory expectations in relation to the authorisation of investment firms

The relocation of a company to the EU means that an authorisation covering the respective business model must be applied for in the respective EU member state. The authorisation procedure must, inter alia, include a description of the company’s organisational structure, including its non-EU branches. The competent authority should be satisfied that the use of the non-EU branch is based on objective reasons linked to the services provided in the non-EU jurisdiction and does not result in situations where such non-EU branches perform material functions or provide services back into the EU, while the office relocated to the EU is only used as a letter box entity. To this end, the competent authority should make its judgement on the substance of the business activity, the organisation, the governance and the risk management arrangements of the applicant in relation to the establishment and the use of branches in non-EU jurisdictions. Therefore, the firm´s program of operations should explain how the relocated EU head office will be able to monitor and manage any non-EU branch, clarify the role of the non-EU branch and provide detailed information, such as:

- an overview of how the non-EU branch will contribute to the investment firm´s strategy;

- the activities and functions that will be performed by the non-EU branch;

- a description of how the firm will ensure that any local requirements in the non-EU jurisdiction do not interfere with the compliance by the EU firm with legal requirements applicable to it in accordance with EU law.

Supervision of ongoing activities of non-EU branches

In order to allow the competent authority to appropriately monitor firms providing investment services or activities on an ongoing basis, firms should provide the competent authority of its home member state with relevant information on any new non-EU branch that they plan to establish or on any material change in the activities of non-EU branches already established. Therefore, the competent authority should, taking into account the importance of non-EU branches for the relevant firm, request on an ad hoc or a periodic basis, information on, inter alia:

- the number and the geographical distribution of clients served by the non-EU branches;

- the activities and the functions provided by the non-EU branch to the EU head office.

Supervisory activity of the competent authority

The competent authority should put in place internal criteria and arrangements to supervise comprehensively and in sufficient depth the activities that branches of EU firms under their supervision perform outside of the EU. For that purpose, the competent authority should prepare plans for the supervision of non-EU branches of EU firms and identify resources dedicated to this activity. These resources should be capable of performing a critical screening of the firms under their supervision that have established non-EU branches, including, information received or requested in relation to these branches.

Upshot

As the Supervisory briefing shows, EU supervisors are urged by ESMA to ensure that companies relocating to the EU as a result of Brexit are not just used as mere letter box entities to gain access to the European single market and the actual investment services are provided via the non-EU branch. Therefore, the competent authorities should take a closer look at the firm´s non-EU branches, to ensure that the branch has the function of a branch not only on paper but also in practice. Investment firms should be prepared for this supervisory practice.