At the turn of the year, there have been some new developments in anti-money laundering (AML) law at both German and EU level. Part 1 of our series dealt with the changes at German law resulting from the implementation of the Fifth EU Anti-Money Laundering Directive. Part 2 sheds some light on the European Banking Authority’s (EBA) new leading role in anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism (CFT).

What is changing in the approach to AML/CFT?

In 2019, the EU legislator gave EBA a legal mandate to preventing the use of the financial system for the purposes of money laundering and terrorist financing and to leading, coordinating and monitoring the AML/CFT efforts of all EU financial service providers and competent authorities. The law implementing EBA´s new powers came into effect on 1 January 2020.

However, assigning EBA a leading role in AML/CFT will not change the EU´s general approach to AML/CFT, which remains based on a minimum harmonisation directive and an associated strong focus on national law and direct supervision of financial institutions by national competent authorities. This reduces the influence and the degree of convergence and consistency EBA´s work can achieve from the outset.

To the extent legally possible, EBA will use its new role to

- lead the establishment of AML/CTF policy and support its effective implementation by competent authorities and financial institutions;

- coordinate AML/CFT measures by fostering effective cooperation and information exchange between all relevant authorities;

- monitor the implementation of EU AML/CFT standards to identify vulnerabilities in competent authorities´ approaches to AML/CFT supervision and to mitigate them before money laundering and financing of terrorism risks materialise.

How will EBA lead on AML/CFT?

To fulfill its new leading role, EBA will focus on two key point: developing an EU-wide AML/CFT policy and ensuring a consistent supervision by national competent authorities. EBA intends to develop such EU-wide AML/CFT policy through standards, guidelines or opinions where this is provided for in EU law as well as on its own initiative where it identifies, for example, gaps in competent authorities´ supervision. In 2020, EBA will be setting clear expectations on the components of an effective risk-based approach with targeted revisions to the core AML/CFT guidelines: the Risk Factors Guidelines and the Risk-Based Supervision Guidelines.

EBA intends to foster a consistent supervision by national competent authorities by assisting them through training, bilateral support and detailed bilateral feedback on their approach to the AML/CFT supervision of banks.

What will EBA do to coordinate?

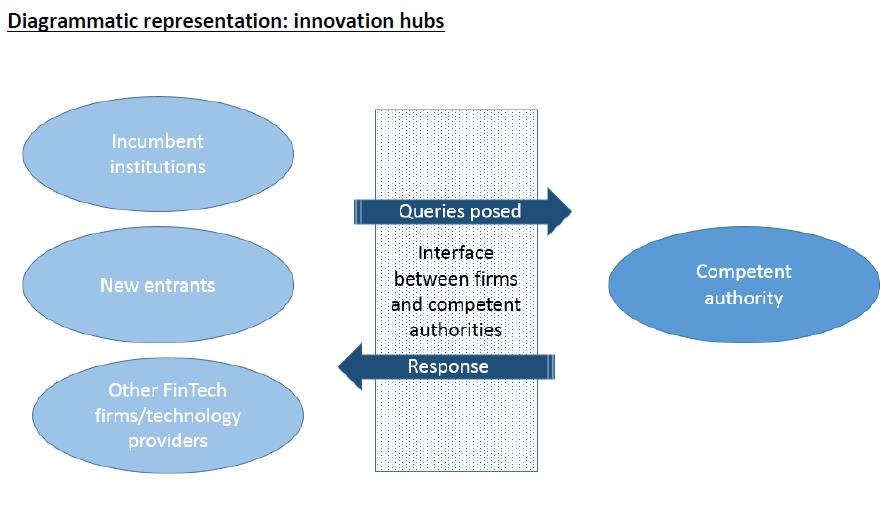

To coordinate the European work against money laundering and terrorism financing, EBA will focus to coordinate national competent authorities´ AML/CFT supervision by fostering effective cooperation and information exchange. To achieve its goal, the EBA will set up a permanent internal AML/CFT standing committee (AMLSC). The AMLSC will bring together, inter alia, representatives of all AML/CFT competent authorities from Member States, along with representatives from ESMA and EIOPA, the Commission and the European Central Bank. Its main task will be to provide subject matter expertise. It will also serve as a forum to facilitate information exchange and ensure effective coordination and cooperation to achieve consistent outcomes in the EU’s work against money laundering and terrorism financing. The AMLSC has met for the first time in February 2020.

In addition to the AMLSC, EBA will create a new AML/CFT database. This database will not only contain information on AML/CFT weaknesses in individual financial institutions and measures taken by competent authorities to correct those shortcomings, but EBA will use it to meet wider AML/CFT information and data need to supports its objectives on AML/CFT work. EBA will draft two regulatory technical standards that will specify the core information that competent authorities must submit to the date base and how EBA will analyse the obtained information and make it available to competent authorities.

What will EBA do to monitor?

One main tool for EBA to monitor the implementation of EU AML/CFT standards will be using information from the new database and to ask national competent authorities to take action if EBA has the indication that a financial institution´s approach to AML/CFT materially breaches EU law. EBA envisages to use this new tool proactively to ensure that AML/CFT risks are addressed by competent authorities and financial institutions in a timely and effective manner. This approach aims to rectify shortcomings at the level of financial institutions; they do not, however, serve to establish whether or not a competent authority may be in breach of Union law.

The difference EBA´s new role will make

As the national implementation of the Fifth European AML Directive and the EBA´s new leading role show, effective AML/CFT measures remain in the focus of the EU legislator, not least due to political developments (terrorist attacks in France, “Panama Papers” etc.). Market participants should prepare themselves for stricter audits by their competent national authorities on AML/CFT compliance. For example, the German Federal Financial Supervisory Authority (Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht – BaFin) has announced AML/CFT as one of its focuses of its supervisory practice for 2020. By assigning a leadership role to EBA, European efforts to prevent money laundering will in future be better coordinated, bundled and consistently implemented throughout the European financial market and therefore, hopefully, be more effective. However, we need to keep in mind that BaFin and subsequently also EBA are only part of the European and national AML regime. In Germany, for example, the FIU has a leading role in AML activities. An overview of the authorities involved can be found here.