On January 7th 2019, the European Supervisory Authorities (ESAs) (consisting of the European Securities and Markets Authority, the European Banking Authority and the European Insurance and Occupational Pension Authority) published as part of the European´s Commission FinTech Action Plan e a joint report on innovation facilitators (i.e. regulatory sandboxes and innovation hubs) available here . The report sets out a comparative analysis of the innovation facilitators established to date within the EU including the presentation of best practices for the design and operation of innovation facilitators.

We take the report as an occasion to present both innovation hubs and regulatory sandboxes in a two-part article. In Part 1 we will discuss what exactly innovation hubs are, what goals they pursue and how they are structured in Germany. Part 2 will then deal with the regulatory sandboxes.

Innovation hubs – What they are and what their goals are

It is often difficult for companies to obtain binding statements on regulatory requirements when a business model is still developing. Innovation hubs create a formal framework that considerably simplifies the exchange between innovators and supervisors, thereby promoting market access.

Innovation hubs provide a dedicated point of contact for firms to raise enquiries with competent authorities on Fin Tech-related issues to seek non-binding guidance on the conformity of innovative financial products, financial services, business models or delivery mechanisms with licensing or registration requirements and regulatory and supervisory expectations. In general, the innovation hubs are available to companies as a user interface at the relevant national authority. In Germany, the innovation hub is located at the Federal Financial Supervisory Authority (Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht – BaFin) and is available here. A total of twenty-one EU Member States have established innovation hubs.[1]

Innovation hubs have been set up to enhance firms´ understanding of the regulatory and supervisory expectations regarding innovative business models, products and services. To achieve this goal, firms are provided with a contact point for asking questions of, and initiate dialogue with, competent authorities regarding the application of regulatory and supervisory requirements to innovative business models, financial products, services and delivery mechanisms. For example, the innovation hubs provide firms with non-binding guidance on the conformity of their proposed business model with regulatory requirements; specifically, whether or not the proposition would include regulated activities for which authorisation is required.

Who can participate and how does an innovation hub work exactly?

In the following, we explain which companies can participate in the innovation hubs and describe how exactly the communication between the companies and the innovation hub takes place.

Scope

The innovation hubs are open to all firms, whether incumbents or new entrants, regulated or unregulated which adopt or consider to adopt innovative products, services, business models or delivery mechanisms.

Communication process between firms and competent authorities

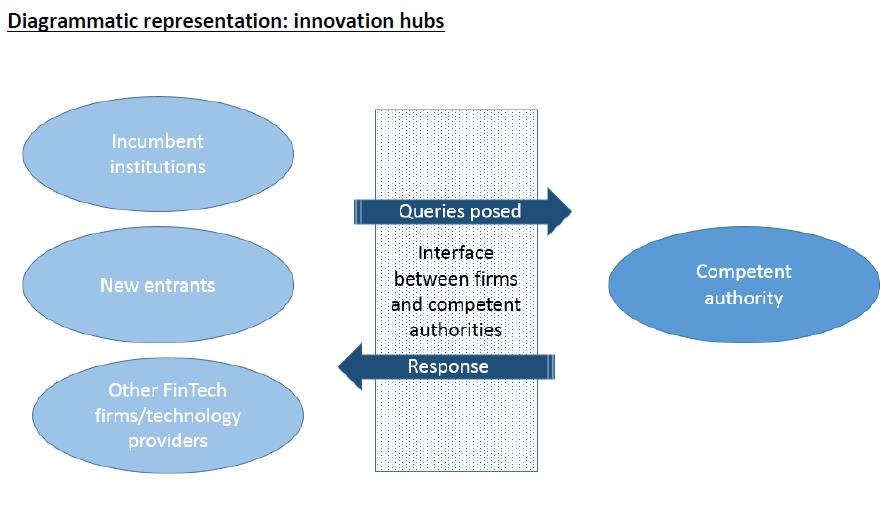

The following ESA graph illustrates the communication process between the firms and the competent authority using the innovation hub. The individual phases of the communication process are explained below. [2]

Submission of enquiries via interface

In order to submit enquiries, all innovation hubs set up in the EU Member States offer interested companies user interfaces through which contact can be established with the respective supervisory authority. This can be done e.g. by telephone or electronically, but also via online meetings or websites. Some innovation hubs also offer the possibility of organising physical meetings. In Germany, BaFin provides an electronic contact form in which both the company data and the planned business model can be presented and transmitted to BaFin. The contact form is available here.

Assigning the request to the relevant point of contact within the competent authority

As soon as the contact has been established and the request has been submitted, typically the authority conducts a screening process to determine how best to deal with the queries raised. In this process, the authority considers factors such as the nature of the query, its urgency and its complexity, including the need to refer the query to other authorities, such as data protection authorities.

Providing responses to the firms

Depending on the nature of the enquiries raised, several information exchanges between the firm and the competent authority may take place. Responses to firms may be routed to different channels such as meetings, telephone calls or email. Typically, the responses provided via the innovation hub are to be understood as preliminary guidance based solely on the facts established in the course of the communications between the firms and the competent authority. The companies can use the information gained to better understand the regulatory requirements for their planned business model and develop it further on this basis.

Follow-up actions

Some authorities offer follow-up actions within their innovation hubs. Especially if the communication process between the company and the authority shows that the business model of the company includes a regulated activity. In this case, some competent authorities may provide support within the authorisation process (e.g. dedicated point of contact, guidance on the completion of the application form).

Previous experiences on the use of innovation hubs

Although innovation hubs are available to all market participants, according to the ESA report, three categories of companies in particular use the innovation hubs: (i) start-ups, (ii) regulated entities that are already supervised by competent authorities and are considering innovation products or services and (iii) technology providers offering technical solutions to institutions active in the financial markets.

Typically, the firms use the innovation hub to seek information about the following: (i) whether or not a certain activity needs authorisation and, if so, information about the licensing process and the regulatory and supervisory obligations, (ii) whether or not anti-money laundering issues arise, and (iii) the applicability of consumer protection regulation and (iv) the application of regulatory and supervisory requirements (e.g. systems and controls).

Upshot

Innovation hubs

provide companies with a good opportunity to interact with regulators via a user-friendly

platform. They can therefore clarify the regulatory requirements for the

products they plan to develop at an early stage and incorporate them into their

business planning. By setting up innovation hubs, especially for young and

dynamic (FinTech-) start-ups, the inhibition threshold to contact the

supervisory authority is significantly lowered, especially because predefined

user interfaces can be used.

[1] Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Germany, Denmark, Estonia, Spain, Finland, France, Hungary, Ireland, Iceland, Italy, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Latvia, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Sweden, UK.

[2] Source: ESA Report FinTech: Regulatory sandboxes and innovation hubs.